The Brush Runs Away with Itself

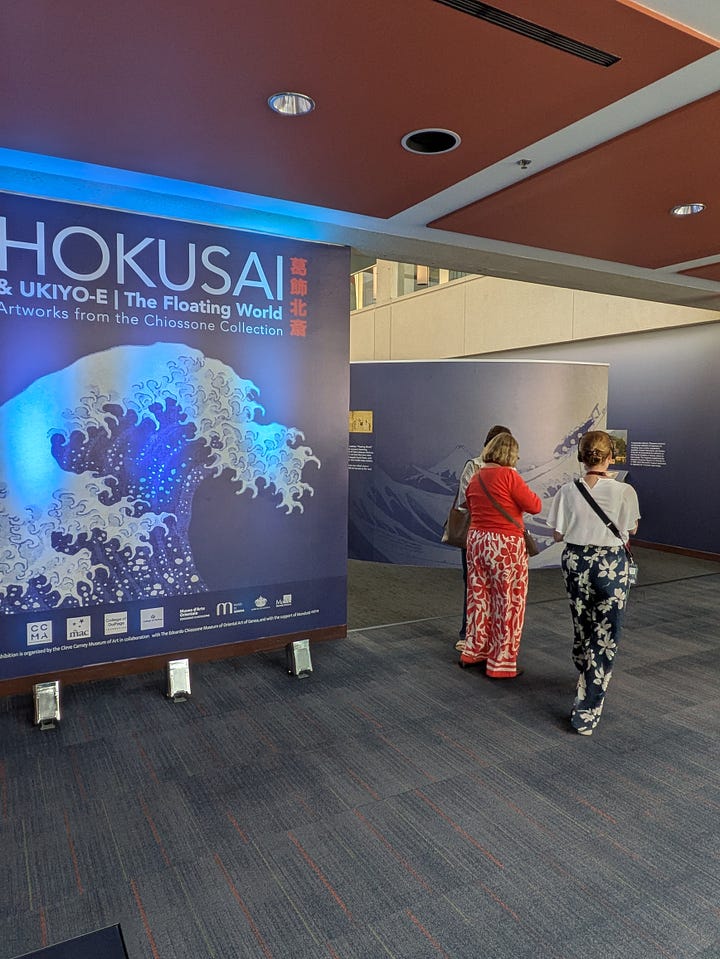

“Hokusai & Ukiyo-e: The Floating World” at Cleve Carney Museum of Art

Hokusai was reportedly the son of a mirror-maker by trade, which seems fitting for a number of reasons, not least that this exhibition quickly makes clear that the experience of seeing his prints (at least for this European-heritage attendee) is a matter of looking at Hokusai, who is looking at the European prints and engravings which drove his style, and reflecting their forms back to the viewer.

His initial fame in Japan was due to the fact that, midway through his career, he took the trouble to track down scarce European landscape artworks (scarce because Japan was closed to international trade in his lifetime) and taught himself the techniques of perspective, lighting and informal composition he found in them. The novelty of his hybrid approach was fascinating to the public, depicting familiar intimate scenes of ordinary life with an alien conception of space and light. To the modern Western viewer, something of that fascination is perceptible, but only because of a reversal, the technique is comfortingly familiar but the milieux and activities are strange and remote in time and temper.

Speaking of the familiar and the strange, it must be noted that this exhibition at the College of DuPage in Glen Ellyn is not only about Japanese art, but also the present and future of museum exhibition itself. It’s certainly no revelation that the social media era is completely rewriting the practices, whys and wherefores of public exhibition of all kinds. But this is the first large-scale example that I can think of that specifically sets as its context the memories and shadows of a dead world. It may be the first that not only presents the future in the windscreen, but (perhaps accidentally) gives a glimpse of the past in the rear-view with some of us inevitably included in the image.

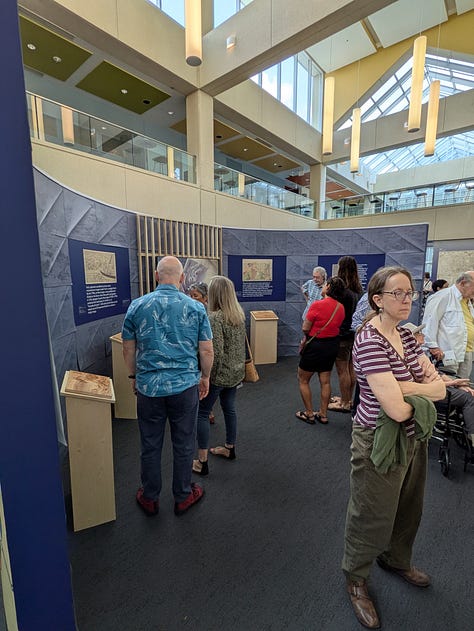

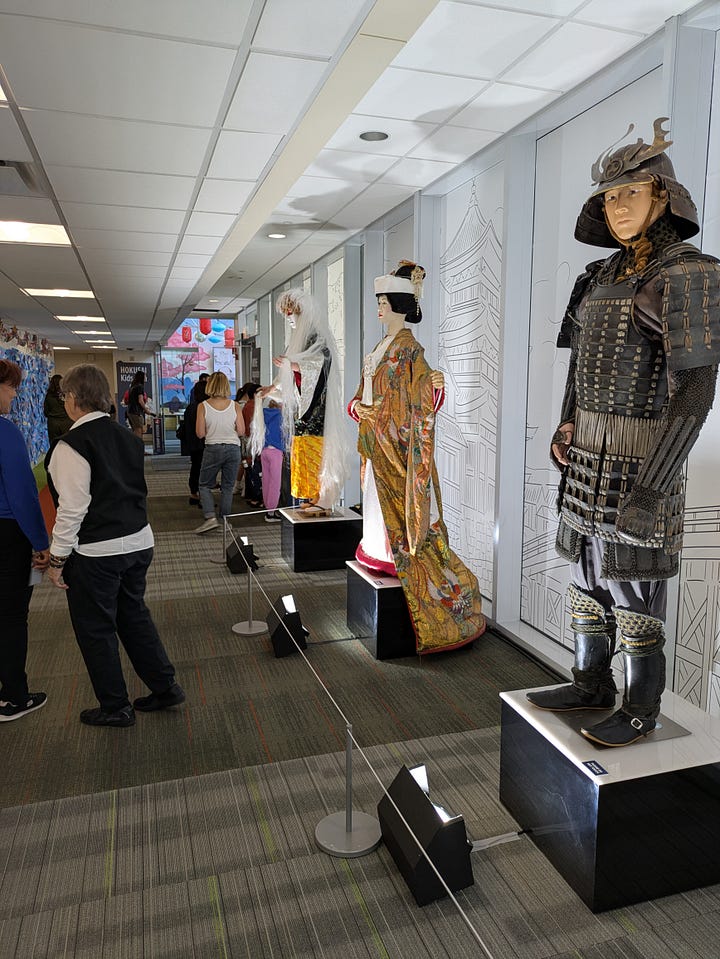

The actual prints of Hokusai and his contemporaries are set discreetly in a side gallery behind glass walls that are covered over with digital graphics. It is overwhelmed by the brassy entrance and enveloping educational displays (which do an admirable job of orienting the visitor). One must make a definite decision to detour into the hall; otherwise, one is easily tracked into the ancillary displays: a life-size re-creation of a street in old Tokyo, a row of mannequins dressed in period Japanese costumes, a crafting playroom for kids, and a tribute to the history of manga executed in cooperation with the owners of the 2d Restaurant in Chicago.

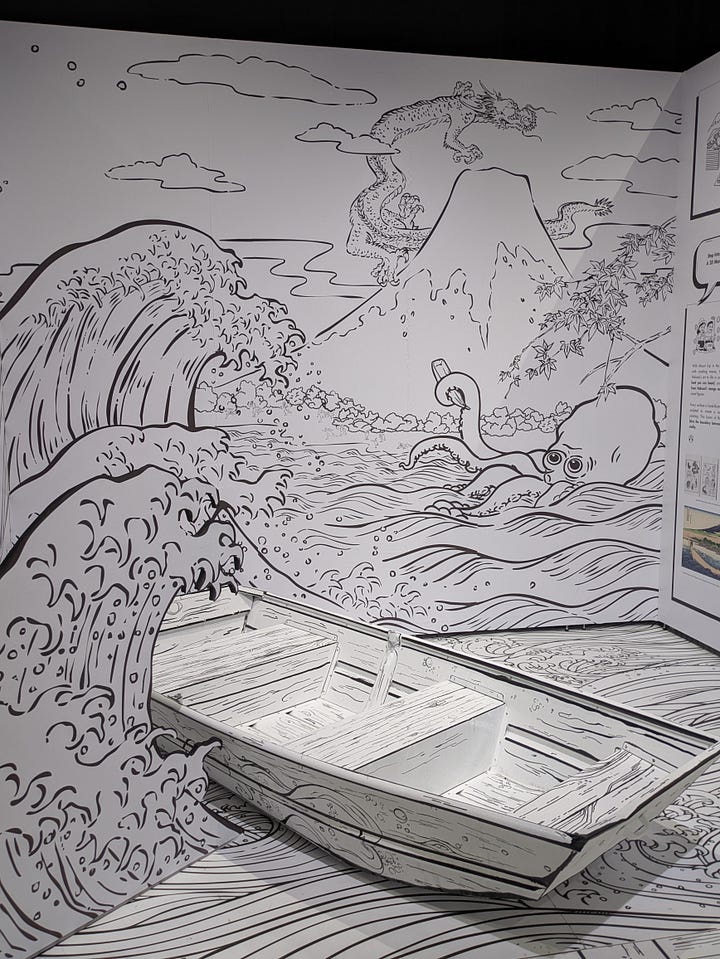

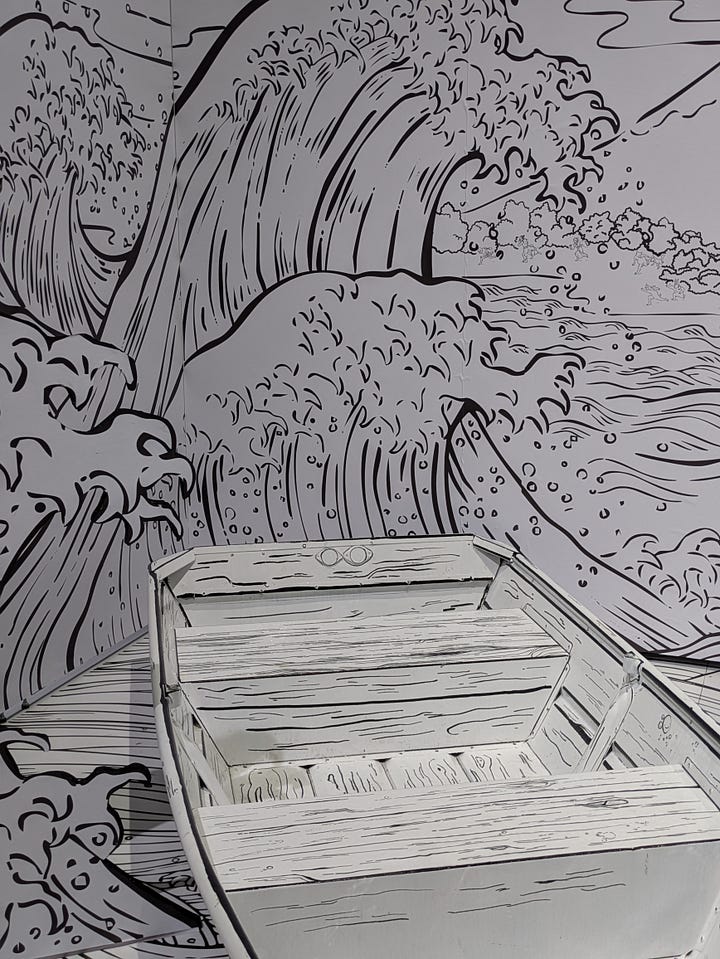

The manga tribute is fitting since Hokusai initiated the tradition in Japan with his notebooks of whimsical drawings, and coined the name (whose original meaning gives this article its title). Among other features, it gives the visitor a chance to get an immersive picture of oneself in a 2d/3d black-and-white version of the Great Wave print itself.

These features are well-executed and excellent for kids, and as a parent I know how desperate one can be to find engaging and enriching activities for the young ones in summer. As part of a community college, the museum is providing a community service and deserves credit for doing so.

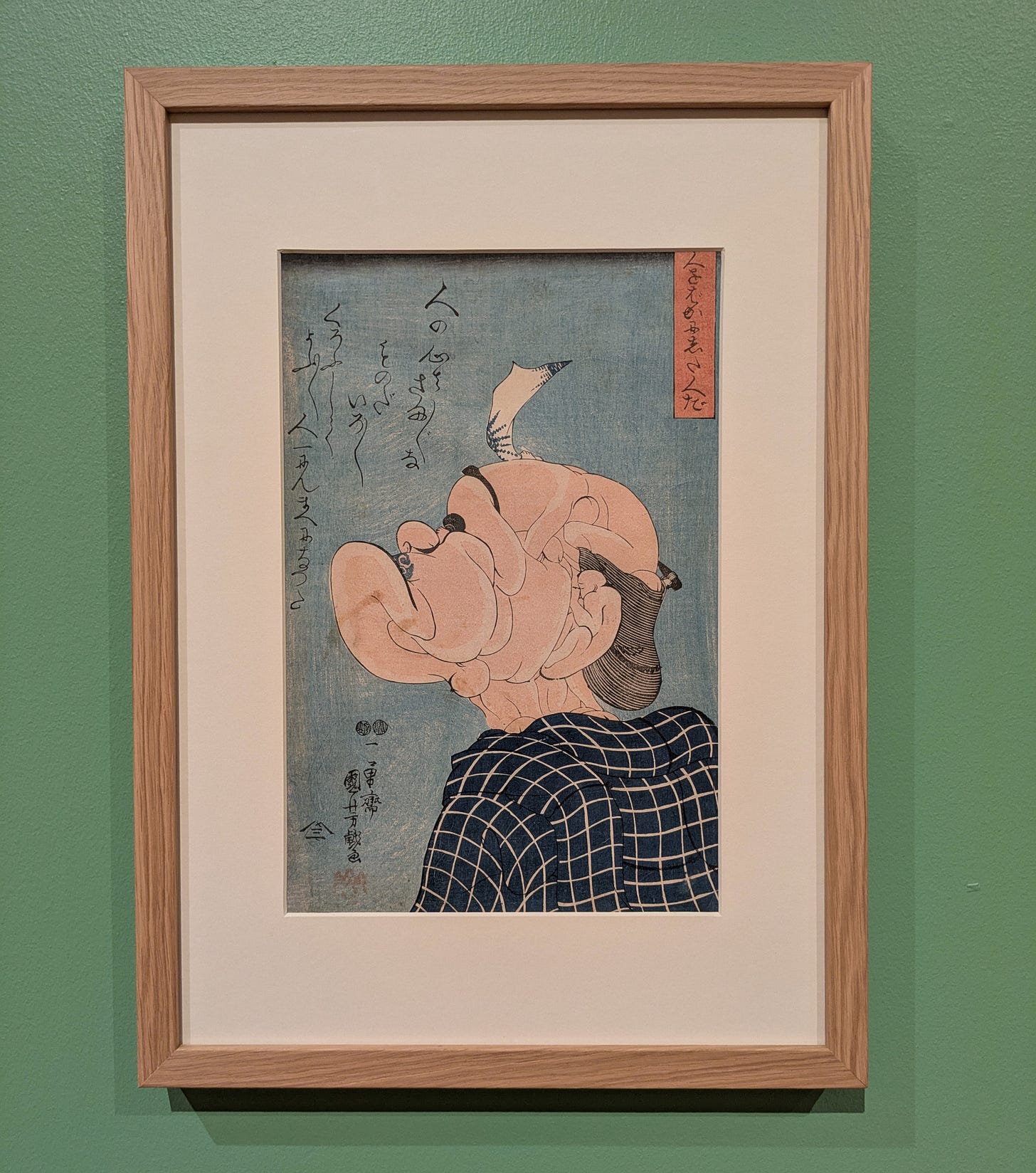

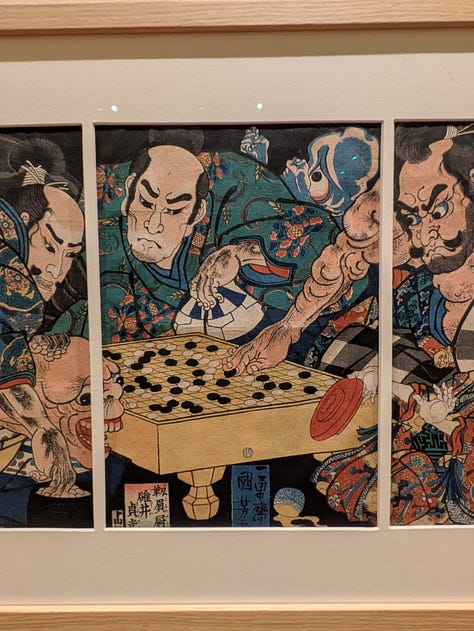

Aside from Hokusai, notable printmakers include in the exhibit are Utamaro, Hiroshige and Utagawa Kuniyoshi. They show the range of aesthetic approaches and social uses expressed in the woodblock print industry of Hokusai’s time, from the familiar to the fantastical to the whimsical.

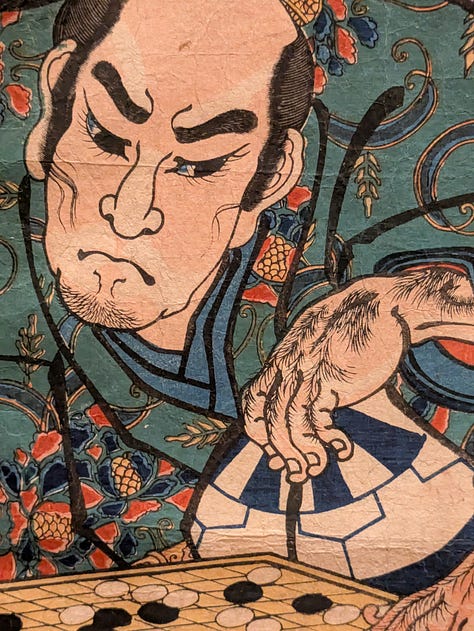

Utagawa Kuniyoshi’s Three Vassals of Yorimitsu depicts legendary warriors attacked by demons while trying to relax at a game.

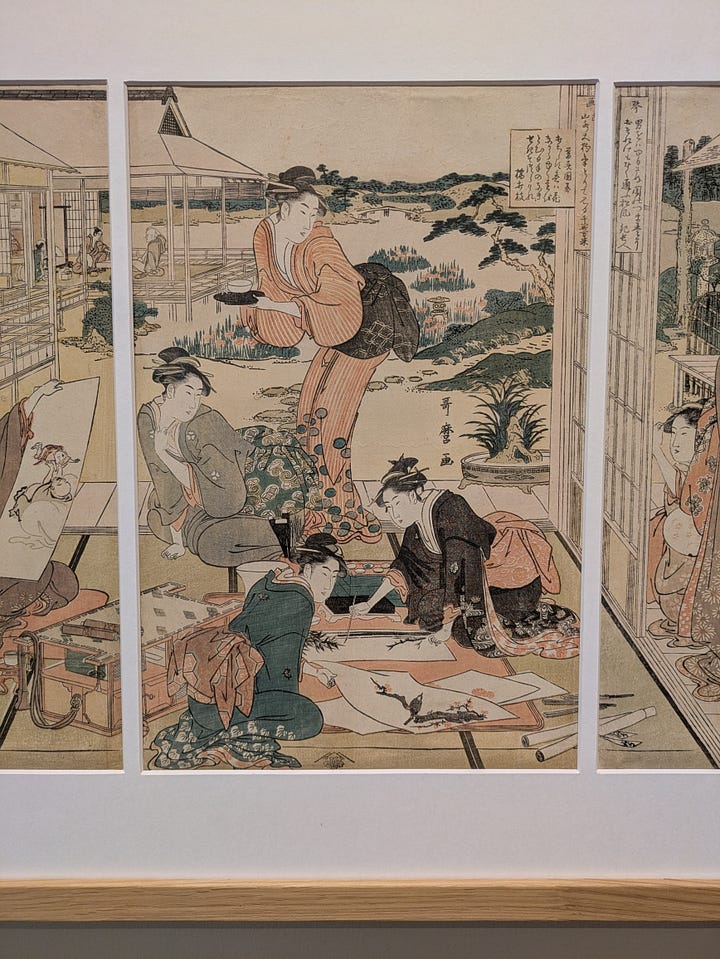

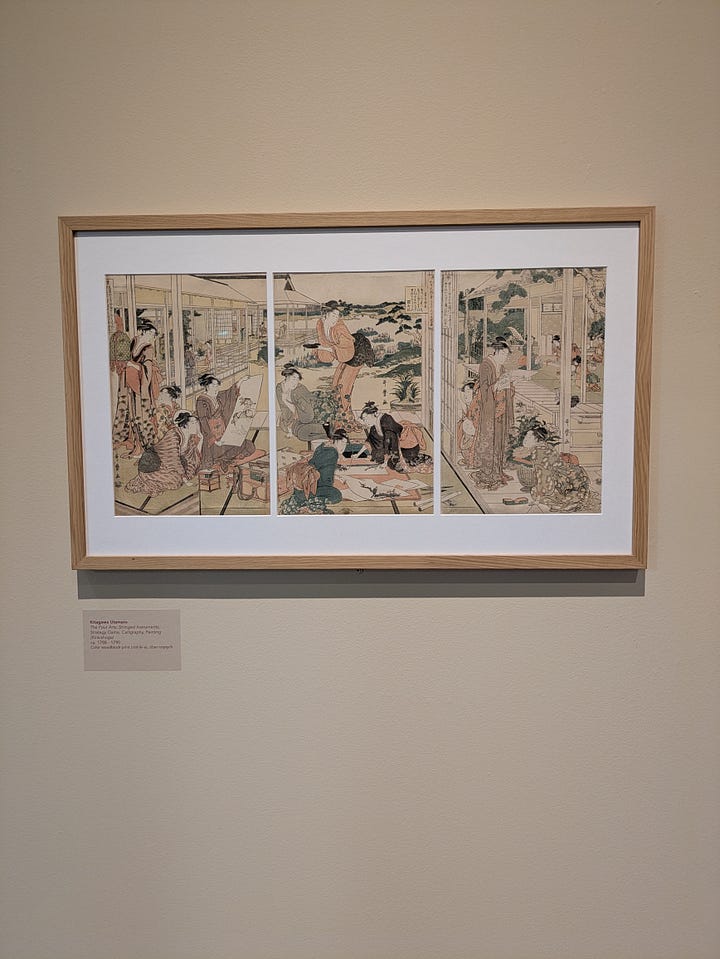

Utamaro’s The Four Arts shows beautiful women engaged in music, calligraphy, painting and gaming.

The above caricatures feature figures whose flesh is composed of smaller human figures.

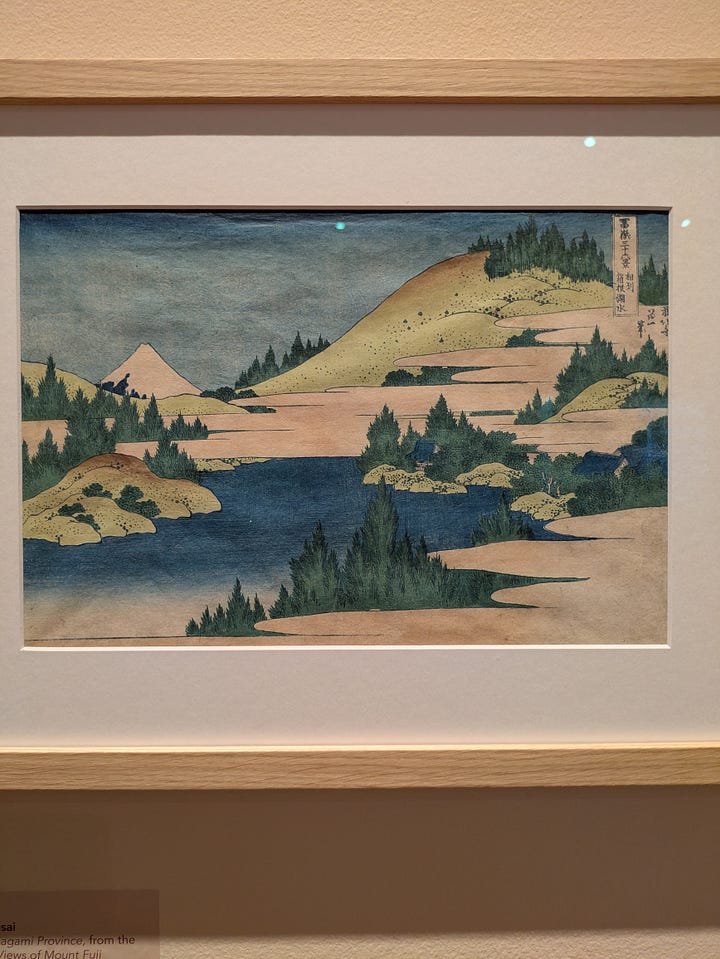

Hokusai’s own prints in the exhibition show the novelty in his work compared with his contemporaries in his use of perspective, lighting and color to produce landscapes that were delightful and comforting in their familiarity, but included the shadow of solitude and alienation; note below the little house among the trees on the island in the lake:

Both facets were taken up by the impressionists in Europe, the heralds of 20th century modernism.

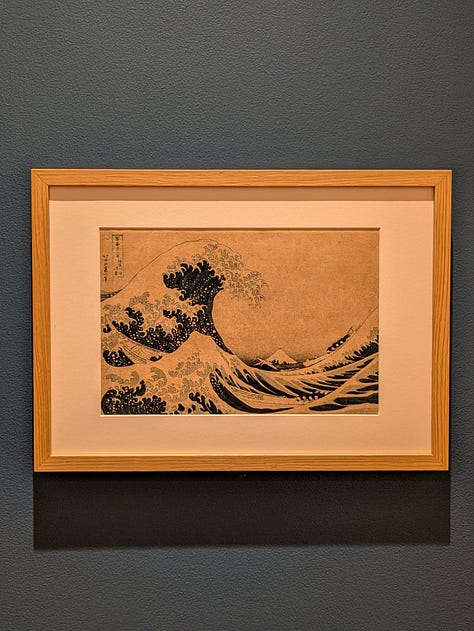

A print of Hokusai’s best-known work, The Great Wave off Kanagawa, is set apart, hung alone on a wall at the end of the gallery, somewhat like the Mona Lisa in the Louvre:

The final lesson in perspective.

If this exhibition is at all about impermanence and change, as the title suggests, then it is as much about the collector, Edoardo Chiossone, as the artist Hokusai and his contemporaries. Hokusai had the good sense and discretion to die, age 89, in 1849, just a handful of years before American Admiral Perry showed up to open Japan to the outside world by force. That visit had vast repercussions, as the Emperor Meiji decided afterward that the country must westernize immediately; among other consequences, the traditional arts and crafts of Japan immediately fell out of fashion and became worthless. The artisans who managed to survive did so by marketing to the demand in Europe and America for the fascinating novelty that their work represented overseas, but those holdovers were nevertheless cut off forever from the rootedness of their artisanship in a living culture.

Chiossone was trained as a commercial printer and engraver in his native Italy amid the vast changes the Industrial Revolution brought to Europe in the mid-19th century. In 1875 he found himself snapped up and spirited away to Japan under the employ of the government there to introduce and deploy the most modern printing technology. He was responsible for engraving and printing Japan’s first postage stamps and paper currency. He stayed there for twenty-four years until his death in 1898 and was buried in Tokyo. There was no going back.

During his life there he avidly collected traditional Japanese arts and crafts of all sorts. The prints in the exhibition were all taken from his collection. His acquisition efforts were relatively simple in that the owners of the art objects were assiduously throwing them away — they had gone out of style and possession of them had become politically inconvenient — and were energetically replacing them with Western products. It is I believe regrettably unrecognized that one of the most powerful and consequential aesthetic experiences one can have is deciding what to leave behind, what to forsake, moreso than what to take. In this context Chiossone was, more importantly than a collector, a witness. Unlike Hokusai he navigated epochal historic change, in two hemispheres. He lived the upheaval that Hokusai imagined. The objects in the exhibition are the jetsam left in the wake of progress.

I have seen other copies of The Great Wave before, both original prints and of course the endless reproductions and derivative works. The composition is masterful, the wave is awesome, Fuji is sublime; but I was drawn in this visit, as I have been on occasions before, to the men in the boats, the ones who bore the terror and paid the price for the aesthetic distillation of the work we are privileged to contemplate in the dim quiet. If the print is in any sense a great work of art, it is because of what those crews saw in the foam and the water that was coming over the wales of their craft: the reflection of their mortality.